The different faces of homelessness

Every person who becomes unhoused has their own story. One-size-fits-all approaches rarely work. The current system can be overwhelming for those trying to find the services that best match their needs. To truly change the trajectory of homelessness and ensure sustainable outcomes, the City, nonprofits, and other community stakeholders must understand the unique challenges people face at every stage of homelessness and consider reforms that address these issues more effectively.

To better understand the current system for people experiencing homelessness, we created six composite characters inspired by real-life stories of people in San Francisco. To protect their privacy, we did not identify anyone directly. Instead, these portrayals reflect the diverse backgrounds, challenges, and aspirations of people who have faced homelessness, drawing from demographic data and insights from people who have lived through it and those who support them.

These fictional characters offer a deeper understanding of the obstacles people face at various stages of homelessness, with the aim of helping the City and service providers craft more tailored solutions. It would be wonderful if, by exploring these stories, stakeholders can identify opportunities for improvement.

Because homeless people in San Francisco are so different—representing a wide range of ages, family situations, and cultural and racial backgrounds—these personas provide an important tool for ensuring that the City tailor its services appropriately.

Maria

45 years old

Maria is 45 years old and a mother of one daughter. After suffering from violent abuse at the hands of her alcoholic husband, Maria and her daughter fled their home. Now Maria is struggling to find stable housing and support for herself and her child.

Cody

39 years old

Cody began living on the streets after his mother died when he was young. Since then, he has struggled with addiction and mental health challenges, cycling in and out of jail for petty crimes. At 39, he has experienced chronic homelessness for nearly 20 years.

Victor

40 years old

After serving in the U.S. military in Afghanistan, Victor suffered an injury that left him unable to walk. When the family business where he worked closed, he became jobless and eventually homeless, grappling with chronic health issues.

Selena

60 years old

Selena is a senior citizen who lived in San Francisco’s Chinatown for over 25 years. After her husband died, her landlord converted their apartment into high-end condos, leading to her eviction. Now, Selena is without a home and struggling with medical issues that have worsened with age.

Frank

34 years old

Frank is 34 and experiencing homelessness for the first time. A physical injury caused him to stop working, leading to unpaid bills and eventually forcing him to leave his apartment. Now living in his car, Frank faces trauma and depression and has developed a substance use disorder.

Yara

18 years old

Yara is a transgender youth. At 18, after facing bullying at school and conflict with their parents, Yara ran away from home. They now live as an unaccompanied youth, searching for a supportive LGBTQ+ community and hoping to finish their education and develop workforce skills.

Frank

34 years old

Frank is 34 and experiencing homelessness for the first time. A physical injury caused him to stop working, leading to unpaid bills and eventually forcing him to leave his apartment. Now living in his car, Frank faces trauma and depression and has developed a substance use disorder.

Yara

18 years old

Yara is a transgender youth. At 18, after facing bullying at school and conflict with their parents, Yara ran away from home. They now live as an unaccompanied youth, searching for a supportive LGBTQ+ community and hoping to finish their education and develop workforce skills.

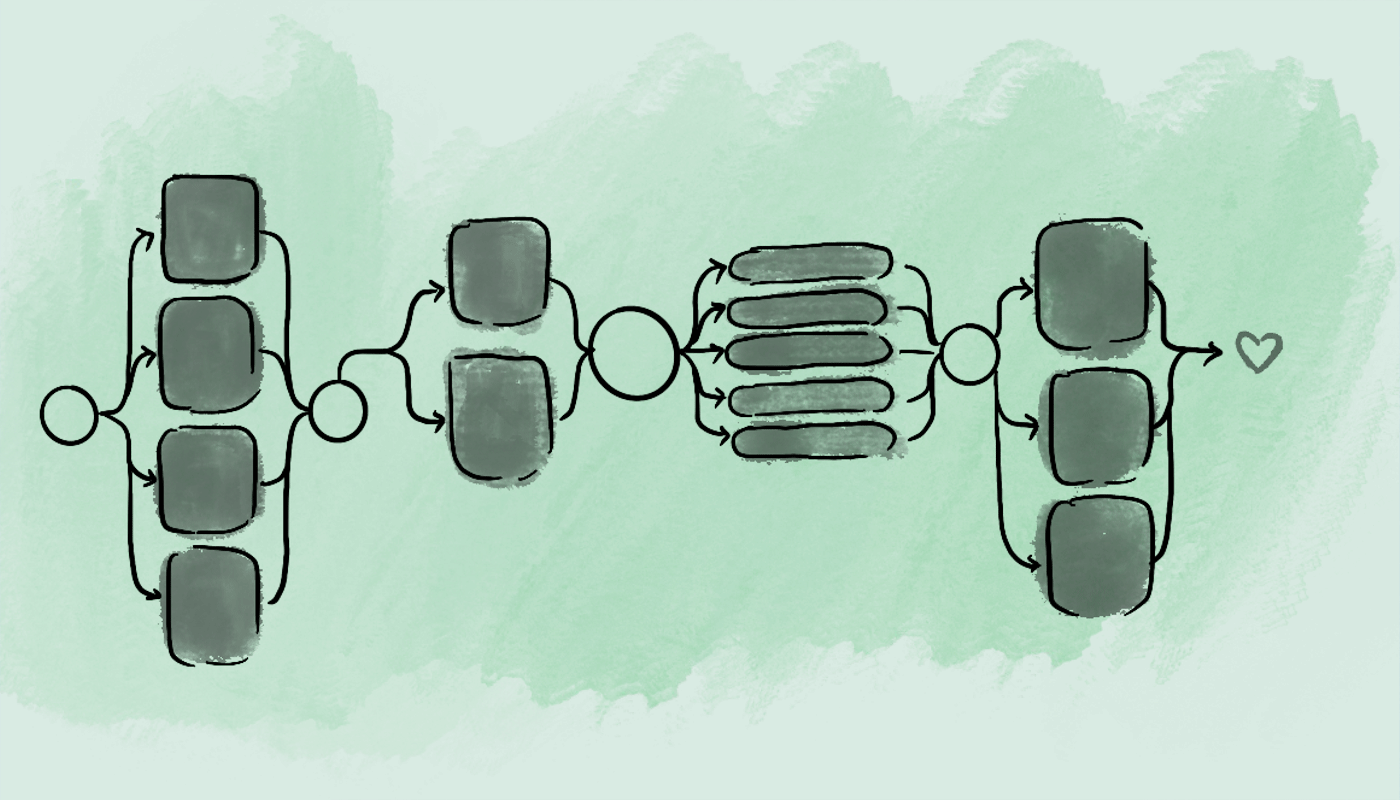

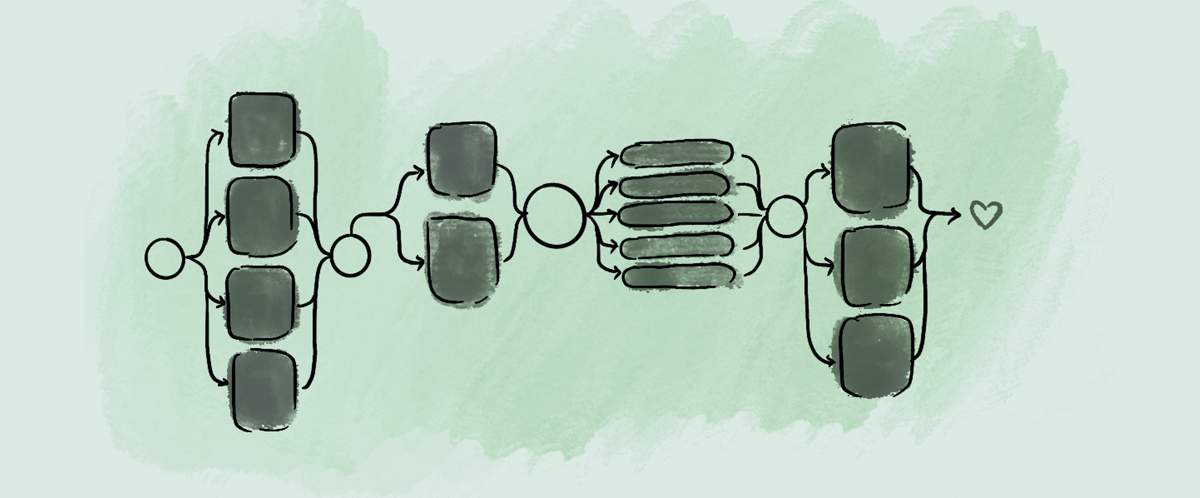

To explore these challenges further, Frank and Yara’s journeys through homelessness have been mapped below to demonstrate how individuals with unique needs and experiences collide with San Francisco’s complex homelessness system.

This graphic highlights three themes. First, it captures Frank and Yara’s unique experiences, showing that the journey through homelessness is rarely straightforward. There are both setbacks and successes, reflecting the challenges people face along the way. Second, this pair of journeys demonstrates how individuals often interact with service providers and must make difficult, confusing decisions about where to seek help. For instance, when Frank experiences extreme trauma and depression, he has more than 20 different mental health service providers to choose from. In today’s system, those most at risk often make these choices without the critical support of a case manager or social worker. Finally, the maps show the connection between City contractors and the people using the services. Providers that are underfunded or overwhelmed by administrative tasks—and are usually unfairly criticized for being inefficient or corrupt—struggle to deliver high-quality care, so people like Frank and Yara can easily fall through the cracks.

The invisible character: the case manager

In the complex maze of homelessness, one vital aspect often goes unnoticed—the case manager. Though invisible to many, case managers are on the front lines, working to solve the puzzle of how to guide people from the streets to stability. Case managers may not be the most visible players in the public eye, but for those experiencing homelessness, they represent a crucial link to hope. Without enough case managers who are adequately supported and compensated, cracking homelessness will be impossible.

San Francisco employs case managers through both City agencies and local service providers, paying them $28–45 an hour. While this might seem reasonable, in a city as expensive as San Francisco, many case managers find themselves classified as low-income. They work in a high-pressure environment, often struggling financially themselves, while shouldering the emotional and logistical weight of helping others.

Best practices suggest one case manager should handle about 15 clients to provide effective, personalized support. Yet many are burdened with caseloads of 30 or more, doubling the work and further complicating their ability to offer meaningful assistance. This overload is a major barrier to solving homelessness.

San Francisco needs to double the number of case managers. But hiring is only part of the solution. The City also needs to rethink how these professionals are deployed, ensuring they can reach the diverse residents who need their support. Effective case management is not just about numbers; it's about distributing resources and empowering case managers with new tools in a way that truly helps untangle the complexities of homelessness.

Many case managers, however, find themselves overworked, underpaid, and demoralized. The burnout is real. It’s making it harder for them to resolve the dire problem they’ve dedicated themselves to. Without significant investment in increasing their numbers, improving working conditions, and providing wages that reflect the cost of living in San Francisco, it’s difficult for these workers to continue doing what they’re passionate about and trained for.

Take, for instance, Camila—a fictional case manager whose story represents the struggles of many. Camila's caseload is overwhelming, yet she is trying to solve homelessness for others while facing her own challenges: financial insecurity, emotional burnout, and a system that stretches her too thin to be effective.

If we truly want to make progress in reducing homelessness, we cannot overlook the role of the case managers. They are not just a minor piece in this complex puzzle; they are key players in resolving homelessness.

Camila began working as a case manager right after graduating from San Francisco State University with a degree in social work. She’s certified by the Commission for Case Manager Certifications and works at a nonprofit organization. She’s responsible for managing over 30 people at any time, many of whom need far more support than she can realistically provide.

In addition to her regular caseload, Camila specializes in bilingual case management. She sets aside time for drop-in clients, which adds to her already packed schedule. Her organization has a long waitlist, so her caseload is consistently heavy. The emotional toll of trying to manage so many clients leaves her feeling drained and on the brink of burnout. Financially, things aren’t much easier. At $30 an hour, her salary doesn’t allow her to live in San Francisco, and her hour-and-a-half long commute adds more stress to her overwhelming workload. Though Camila is devoted to helping people, the constant pressure is making her question whether she can continue doing this work.

This system falls short on multiple fronts. City government struggles to coordinate efforts across departments with overlapping duties and fragmented funding, creating inefficiency. Service providers are left to juggle misaligned funding streams that have competing objectives, making it harder to deliver effective care for people with complex needs. But most critically, the system fails the people it’s meant to serve—those navigating a confusing maze of programs, often without the steady, reliable support they need to break the cycle of homelessness. Without reform, this fragmented approach will continue to fall short where it matters most.

These fictitious characters are based on the most common archetypes of individuals experiencing homelessness in San Francisco, using several sources of insight:

- Data analysis to measure the statistical flow of individuals entering, experiencing, and exiting homelessness

- End-to-end mapping of the journey through homelessness by demographic population, including touchpoints to different service providers

- Interviews with more than 20 civic and nonprofit leaders from frontline service providers

- Synthesized insights from interviews with 28 individuals experiencing homelessness across eight focus groups

Footnotes for Service provider journeys of Frank and Yara

This model is based on external research and assumptions, so actual future outcomes could differ from the estimates provided. The personas were created to represent the most common profiles of people experiencing homelessness in San Francisco. Model creation included analyzing data, mapping individual journeys, and conducting interviews with service providers.

Source: SF.gov; San Francisco Mayor’s Proposed Budget Books; San Francisco Controller’s Adopted Budget Reports; CalHHS; and reports from service providers. Analysis conducted by McKinsey & Company.